University can be one of the most exciting times in a young person’s life; they have the prospect of studying something they are really interested in, meet new people, have new experiences and have a place to make those first adult steps of independence into the world. With all this on offer, why are care experienced young people significantly less likely to go to university and complete their degree than the general population (Jackson 2007)?

The exact numbers of care experienced young people going to university are unclear. Harrison (2017) suggests that the best estimate is that 6% of care-experienced young people (in England; under 21) are in university compared to 43% of their peers in the general population. The difference between the two groups is stark.

Knowing this, it is important to encourage care-experienced young people to attend university to reach their academic potential and access opportunities they are unlikely to have elsewhere. At present this is difficult as there many barriers, notably in the availability of support, encouragement and advice on the pathways to and through university.

One recognised setback is the way that despite the efforts of many social workers the abilities of this group of young people are negatively perceived by professionals and other authority figures in their lives. The impact of such low academic expectations can have negative lasting effects. However, research conducted by Mannay et al. (2015) showed that care experienced young people do express ambition and aspirations to succeed in education and to take up careers that require university level qualification.

So what hinders or helps care-leavers transitioning to, and within university? A doctoral study has explored this question using data from ‘Next Steps’, a study following the progress of young people from England at state or independent secondary schools which involves ‘15, 770 young people, 245 of whom were care-experienced.

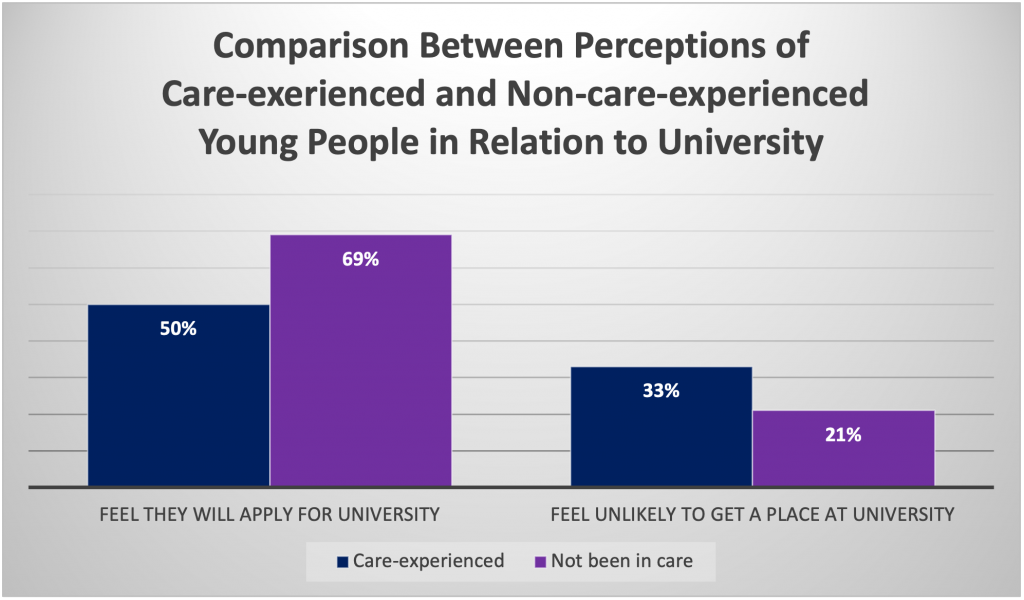

As shown in Figure 1 the findings of this part of the wider study show that young people in care do aspire to go to university but think that their chances of gaining a place are much lower than those who have not been in care. Furthermore, although half of the care experienced young people say they would apply to university, a third felt that it was unlikely they would get a place. This compares poorly with the more than two thirds of those who have not been in care who intend to apply for a university place, and the much lower number who doubted they would achieve a place.

These significant differences between care and non care-experienced young people strongly suggest that being care experienced is linked to lower levels of aspiration to go to university and feelings of whether a place can be gained or not. Mannay et al. (2015) argued that these feelings could arise from a tendency for professionals and carers to dampen care-experienced young people’s aspirations. The pessimistic attitude has also been linked with the lack of knowledge around pathways to university for young people in care, thus denying them access to information that could help them decide whether they would like to attend university or not. The differing policies and arrangements local authorities have in place throughout the UK complicate this matter further.

Collectively, findings from the doctoral study increase concerns about the aspirations and progress of young people in care. These young people have the drive and intellectual capability to thrive in a university setting but are hindered by bureaucratic processes, negative attitudes and low expectations by those who care for them. All these issues need to be addressed to ensure equal opportunities to access university are available and taken. Being care-experienced shouldn’t limit a person’s prospects of attending University.

Author: Gemma Allnatt, Doctoral Student